The Dialogue Problem Is Finally Solved: How AI Made Virtual Patients Work After 50 Years of Trying

By: Boris Rozenfeld, MD, Xuron Chief Learning Officer

That limitation isn’t a flaw in standardized patient training. It’s just reality. Human actors are expensive, require coordination, and can’t scale to give every medical student unlimited practice opportunities. For 50 years, computers promised a solution, but the technology never quite worked. Virtual patients felt artificial, relied on multiple-choice menus instead of real conversation, and cost tens of thousands of dollars to develop [1].

That’s finally changed. We now have data showing that AI-powered virtual patients actually work for medical training, and the technology represents one of the clearest examples of how AI is changing professional education. But the story of how we got here matters, because it explains both why this breakthrough took so long and why it still has significant limitations.

The 50-Year Bottleneck

In 1963, neurologist Howard Barrows trained an actor named Patty Dugger to portray a patient with paraplegia for medical students at Los Angeles County Hospital [2]. The idea of “standardized patients” was revolutionary—every student could practice on the same case in a safe environment. By the 1990s, this became the gold standard for clinical skills training, but standardized patients are expensive, require significant coordination, and can’t scale to give every medical student unlimited practice time.

Computers promised a solution. In 1971, researchers built CASE (Computer-Aided Simulation of the Clinical Encounter), allowing students to type questions and receive responses [4]. But authoring a single case required hundreds of hours and mainframe computing power. By the 2000s, development costs hadn’t improved much. A survey of U.S. medical schools found that many virtual cases cost over $50,000, with production times extending well over a year [1].

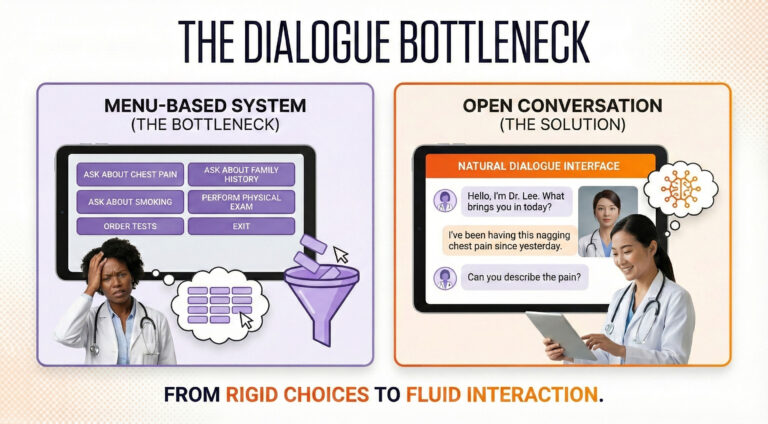

Traditional virtual patients relied on branching logic—essentially complex decision trees where developers had to anticipate every possible question. This created what researchers came to call the “Dialogue Bottleneck” [5,6]. Students were presented with menus: “Ask about chest pain,” “Ask about family history,” “Perform an ECG.”

This menu-driven approach had a subtle but critical flaw. In real consultations, physicians must recall from memory what questions to ask—a high-level cognitive task. But when you present options in a menu, you convert that task from recall to recognition. The menu becomes a cue, artificially scaffolding performance in ways that don’t translate when students face actual patients without prompts [5,6].

Even sophisticated attempts using early natural language processing achieved limited response accuracy—impressive for the era but insufficient for natural conversation [7]. As one systematic review examining communication training put it, barriers “revolved around the lack of authenticity and limited natural flow of language” [5]. Students couldn’t achieve genuine suspension of disbelief when confined to predefined question catalogs.

The LLM Breakthrough

Large language models (LLMs) dissolved this bottleneck overnight. Recent evaluations show current models achieving medical plausibility in the vast majority of patient interactions, with high agreement between AI-generated responses and human expert ratings [8]. Studies have documented dialogue authenticity ratings that experts describe as very good approximations of real conversations with only minor, easily overlooked flaws [9].

The economic transformation is equally dramatic. Those same conversations now cost pocket change with current models [9]. That’s a cost reduction of several orders of magnitude. Once you write the prompt defining a virtual patient’s personality and symptoms, you can deploy it to thousands of students simultaneously at near-zero marginal cost [10].

But does it actually teach? Here’s where the evidence gets interesting.

What Actually Works

A meta-analysis synthesized dozens of randomized controlled trials with thousands of participants [10]. It showed that virtual patients produced large effects, favoring them over traditional education for skills outcomes. Breaking this down, the majority of analyses showed improvement in data gathering, diagnosis, and patient management [11].

Recent trials testing LLM-powered systems show similar results. Studies have found intervention groups significantly outperforming controls on clinical reasoning and decision-making measures [12]. The improvements are consistent and measurable.

The most revealing study compared AI simulators directly against human actors. A UK multicenter randomized trial tested an AI-driven voice simulator versus traditional actor-based training [13]. Both methods significantly improved communication skills. Actor-based training led to slightly higher gains and higher student satisfaction. But here’s the economics: the AI training cost roughly half as much as human actors.

Translation: AI virtual patients are “non-inferior” at roughly half the cost. For now, not better, but good enough to massively expand access to practice. With the growing speed of AI capability, the efficacy of AI virtual humans will dramatically improve as well.

Human Standardized Patients Aren't Going Anywhere

Let me be clear: human standardized patients (SPs) remain essential and will continue to be for the foreseeable future. Live actors bring nuance, emotional authenticity, and the irreplaceable element of genuine human connection that no AI can fully replicate. For high-stakes assessment, complex emotional scenarios, and teaching advanced communication skills, human SPs are still the gold standard.

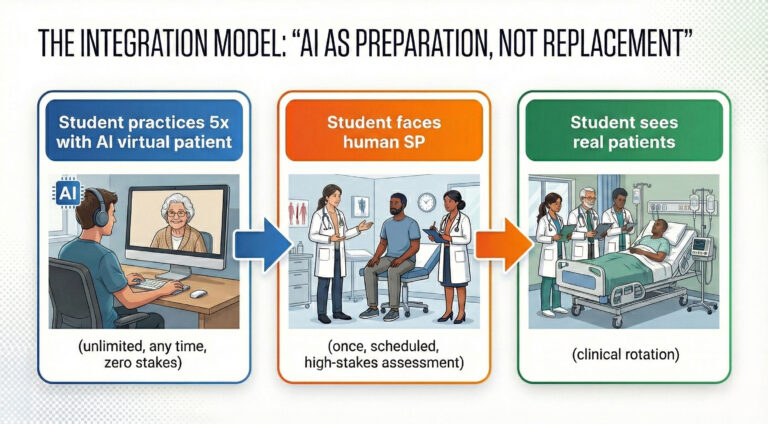

The real value of AI virtual patients isn’t replacement, it’s preparation. Human SP sessions are resource-intensive. They require scheduling, dedicated space, trained actors, and faculty oversight. Most importantly, students typically get one shot at each scenario. If they miss critical questions or handle the encounter poorly, they don’t usually get a do-over.

AI virtual patients solve this by enabling unlimited deliberate practice. Students can attempt the same motivational interviewing case five times before facing a human SP, learning from their mistakes in a zero-stakes environment. They can practice breaking bad news at 2 AM when they can’t sleep, thinking about an upcoming exam. When they finally encounter the human SP, they’re vastly better prepared, making that expensive, limited resource far more effective.

This is the proper role of AI in medical education: a force multiplier for human teaching, not a substitute for it.

The Interface Actually Matters

Not all virtual patients are created equal. A randomized study comparing text-based chatbots to anthropomorphic 3D avatars found the simple text chatbot scored significantly higher on usability [14]. However, the fact that digital human users reported more nervousness is actually a feature, not a bug.

Real clinical encounters make people nervous. When students interact with embodied avatars that trigger authentic anxiety responses, they’re experiencing something closer to what they’ll feel with human standardized patients, and eventually, with real patients. The ability to practice managing that nervousness in a completely safe environment, where mistakes have no consequences, is invaluable. Students can learn to regulate their anxiety, maintain their clinical reasoning under pressure, and develop confidence through repeated exposure. By the time they face a human SP or walk into an actual exam room, that physiological stress response is familiar territory they’ve learned to work through.

This counterintuitive finding reveals something important: elaborate technology doesn’t automatically improve learning, but when it creates psychological conditions that mirror real practice, it can enhance training [5,13].

Text-based systems work well for clinical reasoning—forcing students to formulate precise questions and allowing reflection time. Voice adds realism and lets students practice spoken communication, though latency issues can disrupt flow. Embodied avatars excel at teaching recognition of non-verbal cues like facial expressions and body language, critical for complex emotional scenarios, while also providing that beneficial stress inoculation [14,15]. The best choice depends on the learning objective, not on which technology seems most impressive.

The Limitations You Need to Know

The safety concerns with virtual patients are real but manageable. The most documented issue is hallucination, where LLMs sometimes generate factually incorrect information. Studies have found substantial baseline error rates, though these can be significantly reduced with careful prompt engineering. Algorithmic bias also requires vigilance, with research documenting disparate treatment recommendations based on patient demographic characteristics [18]. If students train extensively on biased virtual patients, their implicit biases get reinforced rather than challenged. Current implementations also can’t fully teach nonverbal communication, and some evaluations have noted issues with verbosity, excessive agreeability, and dialogue quality degrading over extended conversations [9].

The Latest Models and What's Coming

The pace of improvement is breathtaking. The latest generation of language models shows substantial advances over even the systems evaluated in recent studies. Response coherence has improved, verbosity issues are diminishing, and the models better maintain consistency across longer conversations. Importantly, AI development is not slowing down anytime soon!!! The field continues to see rapid progress in areas like multimodal understanding, emotional intelligence, and reduction of hallucination rates.

Many limitations we observe today will likely be resolved within the next few of years. Voice latency is approaching imperceptible levels. Bias mitigation techniques are becoming more sophisticated. This isn’t speculation. It’s the observed trajectory of the past few years accelerating forward.

Future development will likely bring longitudinal virtual patients where students follow the same patient over time, witnessing disease progression and consequences of their decisions [19]. This addresses a major gap where students rarely see long-term outcomes of their interventions. We’ll also see multimodal integration where virtual patients perceive learners’ non-verbal behavior through webcams and adjust responses accordingly [3].

The next few years should bring standardized outcome measures and curriculum frameworks as virtual patients move from pilot projects to formal integration in medical school curricula [3]. Medical-specialty-tuned language models will likely reduce error rates and bias issues further.

The Bottom Line

Virtual patients demonstrate large effects on clinical skills and reasoning, achieve high levels of medical plausibility at dramatically reduced costs, and work effectively across different modalities when paired with sound instructional design [8,10]. But no randomized trials directly compare LLM-powered virtual patient training to traditional standardized patient training for learning outcomes. Long-term retention, transfer to actual clinical encounters, and equivalence for high-stakes assessment remain unstudied [9].

The field is extraordinarily young, with the vast majority of studies on LLM virtual patients were published in the past two years [3]. Only a small fraction of studies used validated evaluation tools, and only a minority objectively measured learning outcomes.

The apprenticeship model isn’t dead. It’s evolving. And after 50 years of trying to make virtual patients work, we finally have the technology and the evidence to show they actually do—with appropriate caveats, proper implementation, and human standardized patients remaining central to the educational experience.

References

- Huang G, Reynolds R, Candler C. Virtual patient simulations at U.S. and Canadian medical schools. Acad Med. 2007;82(5):446-451.

- Barrows HS. An overview of the uses of standardized patients for teaching and evaluating clinical skills. Academic Medicine. 1993;68(6):443-451.

- Zeng J, Li M, Wang L, et al. Embracing the future of medical education with large language model-based virtual patients: scoping review. J Med Internet Res. 2025;27:e79091.

- Harless WG, Drennon GG, Marxer JJ, Root JA, Miller GE. CASE: a computer-aided simulation of the clinical encounter. J Med Educ. 1971;46(5):443-448.

- Lee J, Kim H, Kim KH, et al. Effective virtual patient simulators for medical communication training: a systematic review. Med Educ. 2020;54(9):786-795.

- Cook DA, Triola MM. Virtual patients: a critical literature review and proposed next steps. Med Educ. 2009;43(4):303-311.

- Maicher K, Danforth D, Price A, et al. Developing a conversational virtual standardized patient to enable students to practice history-taking skills. Simul Healthc. 2017;12(2):124-131.

- Holderried F, Schneider J, Rieder J, et al. A language model-powered simulated patient with automated feedback for history taking: prospective study. JMIR Med Educ. 2024;10:e52540.

- Cook DA, Sherbino J, Durning SJ. Virtual patients using large language models: scalable, contextualized simulation of clinician-patient dialogue with feedback. J Med Internet Res. 2025;27:e68486.

- Kononowicz AA, Woodham LA, Edelbring S, et al. Virtual patient simulations in health professions education: systematic review and meta-analysis by the digital health education collaboration. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(7):e14676.

- Plackett R, Kassianos AP, Mylan S, et al. The impact of virtual patients on medical students’ clinical reasoning: systematic review. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):558.

- Schmidt M, Schaper M, Wrona KJ, et al. Large language models improve clinical decision making of medical students through patient simulation and structured feedback: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Med Educ. 2024;24(1):1339.

- Tyrrell EG, King J, Hornsey A, et al. Web-based AI-driven virtual patient simulator versus actor-based simulation for teaching consultation skills: multicenter randomized crossover study. JMIR Form Res. 2025;9:e71667.

- Thunström AO, Steingrimsson S. Usability comparison among healthy participants of an anthropomorphic digital human and a text-based chatbot as a responder to questions on mental health: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Hum Factors. 2024;11:e51949.

- Stevens A, Hernandez J, Johnsen K, et al. The use of virtual patients to teach medical students history taking and communication skills. Am J Surg. 2006;191(6):806-811.

- Ochs M, Blache P, Saubesty J, et al. Embodied virtual patients as a simulation-based framework for training clinician-patient communication skills. Front Virtual Reality. 2022;3:827312.

- Borg A, et al. Virtual patient simulations using social robotics combined with large language models for clinical reasoning training. J Med Internet Res. 2025;27:e63312.