AI Feedback Is Solving Medicine’s Oldest Teaching Problem

Medical education has a feedback problem. And we’ve known about it for 40 years.

Back in 1983, Jack Ende wrote a paper that established feedback as essential for guiding learner performance.[1] He also explained why vague praise or delayed comments fail to change behavior. We’ve known this since Reagan was president. The solution seemed obvious: observe students more, give better feedback. Except we never did it.

A multiyear analysis of hospital training rotations showed the brutal reality. Many students reported never being directly observed by teachers for core parts of the patient visit. Not the complete physical exam. Not asking about medical history.[2] Without observation, meaningful feedback becomes impossible. Teachers cite limited time and competing hospital duties as the barriers.[3] Despite decades of attention, reviews still describe a gap between what effective feedback requires and what learners reliably receive.[4]

This is the feedback gap. And I experienced it firsthand during medical school training.

The First Revolution: Simulation

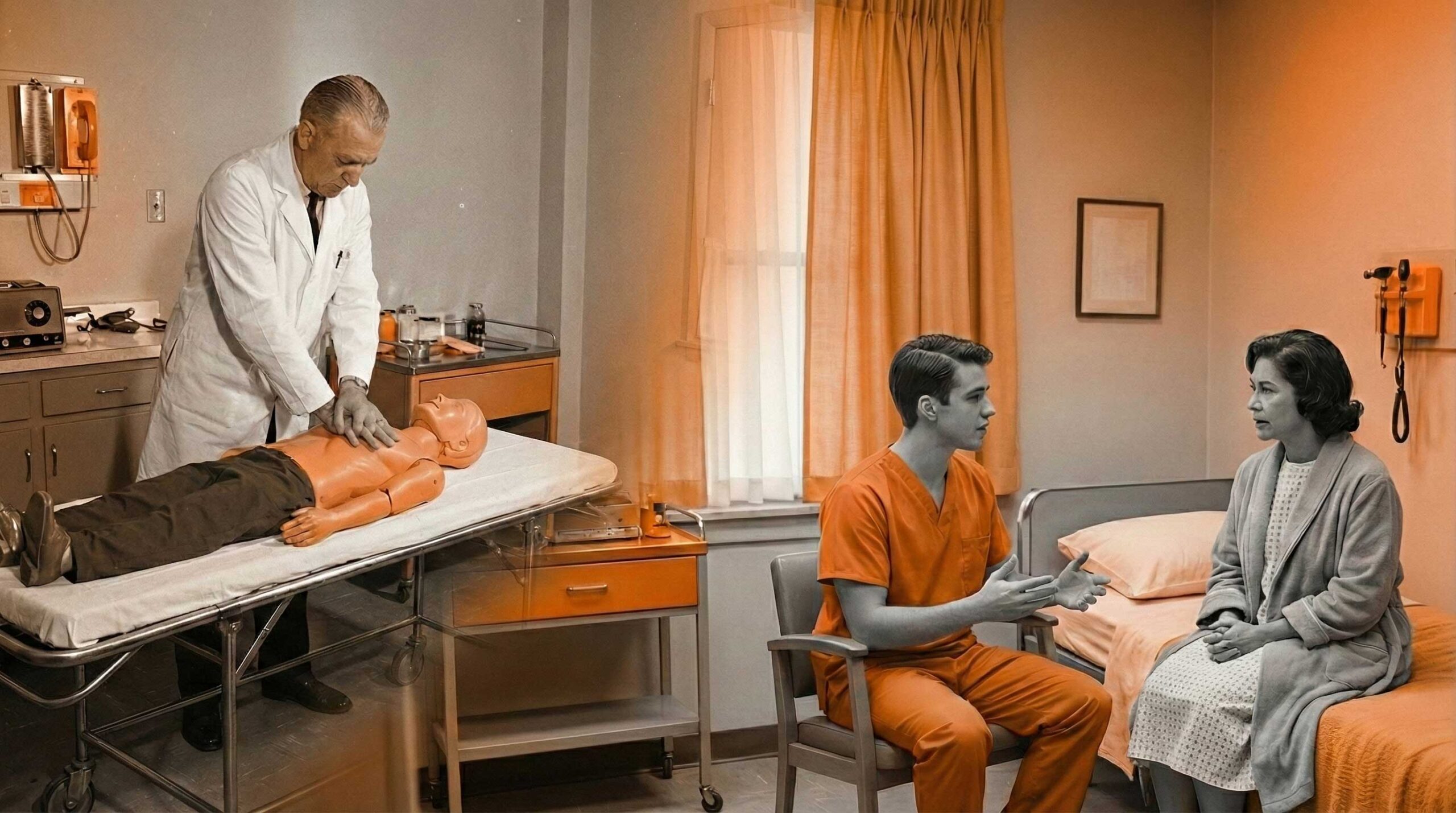

Simulation transformed how feedback could be delivered by making practice repeatable without putting patients at risk. Training with mannequins enabled deliberate practice with immediate body responses and structured review sessions.[5]

Trained actors playing patients (called standardized patients or SPs) added structured observation of communication, empathy, and professionalism. The SP method traces back to early “programmed patient” work in the 1960s.[6] Research shows that formats using trained actors outperform mannequins on knowledge outcomes in certain scenarios.[7]

The development of structured medical exams (OSCEs) in 1975 combined these tools into assessment stations designed to improve reliability across learners and settings.[8]

But simulation didn’t solve the problem. It made it more expensive.

OSCEs and SP encounters still require trained observers, actors playing patients, scoring, and feedback delivery. That dependency creates limits on how many students can be trained and contributes to delays between performance and feedback.[9] The practical challenge between workable assessment processes and the level of feedback learners need remained unsolved.

The AI Revolution: What's Different This Time

AI is changing who delivers feedback, how detailed it gets, and how quickly learners receive it. Several technical approaches are converging right now.

Automated Performance Scoring

AI systems that analyze video extract objective performance signals that humans miss in real time. This includes detailed movement measurements and efficiency measures in robotic surgery.[10] Advanced AI programs recognize surgical actions at high accuracy and support skills assessment processes that would otherwise require extensive expert review.[11] Instrument movement features predict expert-rated technical skill, which supports scalable, consistent coaching.[12]

AI for Analyzing Communication

AI systems that understand language score communication behaviors at scale. This includes empathy-related and patient-centered behaviors using automated scoring tools designed for educational settings.[13] A broad review of empathy recognition shows a growing evidence base for measuring empathy-related language features, while highlighting limitations in how well these tools work across different situations.[14]

AI Chatbot-Style Feedback

AI chatbot-like systems generate written coaching and targeted suggestions from learner performance. A research study of an AI-powered virtual patient demonstrated structured, automated feedback for taking medical histories with strong agreement with doctor ratings.[15] Work evaluating AI chatbot use in assessment reports high agreement between automated grading and teacher scoring for documentation after patient encounters, with large reductions in human grading effort.[16]

The Benefits Are Real

Unprecedented Scalability

AI systems evaluate large numbers of learners without needing more teachers to watch them. This directly addresses the growth limitation in trained actor and structured exam formats. You want to train 500 students? 5,000? The extra cost approaches zero.

Consistency and Fairness

AI applies the same scoring logic each time, reducing differences between graders. Research across multiple medical schools on surgical AI emphasizes that reliability and fairness must be checked explicitly, not assumed.[17] But when done right, AI removes the bias of a tired teacher at 5 PM grading differently than at 9 AM.

Immediate Feedback Loops

When feedback is delivered close to performance, it supports faster learning. Training literature emphasizes the educational value of structured feedback as part of the learning cycle, especially when tightly connected to the observed performance.[18] This is basic learning science. AI makes it possible at scale.

Longitudinal Performance Tracking

AI makes it practical to store performance records across encounters and create profiles over time. Research describes how automated assessment supports ongoing skill development when paired with appropriate supervision and teaching design.[19]

The Limitations Are Also Real

Algorithmic Bias and Equity

Bias enters across the AI development process and produces different performance for different groups of people. A recent review outlines how bias arises in features, labels, evaluation choices, and real-world use. It emphasizes reducing bias through diverse data, careful evaluation, understandable systems, and validation before use.[20]

Accuracy and Hallucination Concerns

AI chatbots generate smooth-sounding but incorrect content. In education, this creates risk when learners accept outputs without questioning them or when automated feedback is presented without transparency about uncertainty and limits. This is a design and supervision problem, not only a technology problem.

The Irreplaceable Human Element

AI does not replace human judgment about professionalism, situation-specific decision making, and the ethical and relational dimensions of care. Skills-focused training programs still require human coaching, direct observation in real settings, and teacher development to interpret performance meaningfully and support growth.[21]

The Future: Augmentation, Not Replacement

The most sensible path forward is enhancement, not replacement. Use AI for first-line scoring, pattern detection, and rapid feedback. Reserve teacher time for complex judgments, detailed coaching, and mentorship.

Combined approaches that merge AI-driven feedback with expert instruction are already being studied, and they are likely to expand as tools mature and evaluation standards improve.[22]

As implementation becomes more practical, access to high-quality feedback should become less dependent on local staffing depth and geography. Health systems are already exploring workforce and education use cases that depend on scalable assessment and coaching infrastructure.[23] This is the direction of travel even if the best model designs are still evolving.

The feedback gap that Jack Ende described in 1983 remained unsolved through mannequins, standardized patients, and OSCEs. AI might finally close it. Not by replacing human teachers, but by making their expertise scalable.

Teacher time is finite. The number of learners who need feedback is not. AI changes that equation.

References

- Ende J. Feedback in clinical medical education. JAMA. 1983;250(6):777-781.

- Howley LD, Wilson WG. Direct observation of students during clerkship rotations: a multiyear analysis. Acad Med. 2004;79(3):276-280.

- Burgess A, van Diggele C, Roberts C, Mellis C. Feedback in the clinical setting. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(Suppl 2):460.

- Stowers K, Timme K, Giardino A. Feedback in Clinical Medical Education: Then vs. Now. Med Res Arch. 2024;12(12).

- Cooper JB, Taqueti VR. A brief history of the development of mannequin simulators for clinical education and training. Postgrad Med J. 2008;84(997):563-570.

- Barrows HS, Abrahamson S. The programmed patient: a technique for appraising student performance in clinical neurology. J Med Educ. 1964;39(9):802-805.

- Alsaad AA, Bhide V, Moss JL, de Focatiis P. Simulated patient and objective structured clinical examination: a comparative study between simulated patient and mannequin. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2017;8:701-704.

- Harden RM, Stevenson M, Downie WW, Wilson GM. Assessment of clinical competence using an objective structured clinical examination (OSCE). Br Med J. 1975;1(5955):447-451.

- Burgess A, Mellis C. Feedback and assessment for clinical placements: achieving the right balance. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2015;6:373-381.

- Baek S, Kim E, Vemuru V, et al. Using artificial intelligence and computer vision to analyze technical proficiency in robotic surgery. Surg Endosc. 2023;37(5):3593-3600.

- Hashemi N, Haddad M, Escandarani S, et al. Video-based robotic surgical action recognition and skills assessment on porcine models using deep learning. Surg Endosc. 2025;39(3):1709-1719.

- Azari DP, Radwin RG, Lindberg LE, et al. Predicting surgeon technical skill from clinical instrument motion in robot-assisted surgery. Ann Surg. 2019;269(3):574-581.

- Rezayi S, et al. Automated scoring of communication skills in physician-patient interaction: balancing performance and scalability. In: Proceedings of the 20th Workshop on Innovative Use of NLP for Building Educational Applications (BEA 2025). Association for Computational Linguistics; 2025:891-897.

- Shetty A, Durbin J, Weyrich MS, Martinez AF, Qian J, Chin C. A scoping review of empathy recognition in text using natural language processing. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2024;31(3):762-775.

- Holderried F, et al. A language model-powered simulated patient with automated feedback for history taking: prospective study. JMIR Med Educ. 2024;10:e59213.

- Thomas A, et al. Evaluating the Effectiveness of ChatGPT Versus Human Proctors in Grading Medical Students’ Post-OSCE Notes. Fam Med. 2025;56(10):803-810.

- Kiyasseh D, et al. A multi-institutional study using artificial intelligence to provide reliable and fair feedback to surgeons. Commun Med (Lond). 2023;3:42.

- Huang X, et al. The impact of simulation-based training in medical education: a review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2024;103(27):e38697.

- Sriram A, Ramachandran K, Krishnamoorthy S. Artificial Intelligence in Medical Education: Transforming Learning and Practice. Cureus. 2025;17(3):e80852.

- Cross JL, Choma MA, Onofrey JA. Bias in medical AI: Implications for clinical decision-making. PLOS Digit Health. 2024;3(11):e0000651.

- Lee J, Chiu A. Assessment and feedback methods in competency-based medical education. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2022;128(3):256-262.

- O’Connor R, et al. Combining real-time AI and in-person expert instruction in simulated surgical skills training: randomized crossover trial. npj Artif Intell. 2025;1(1):36.

- Penn Medicine News. Can AI tools help train a more effective physician? Published January 13, 2026. Accessed January 21, 2026.